|

|

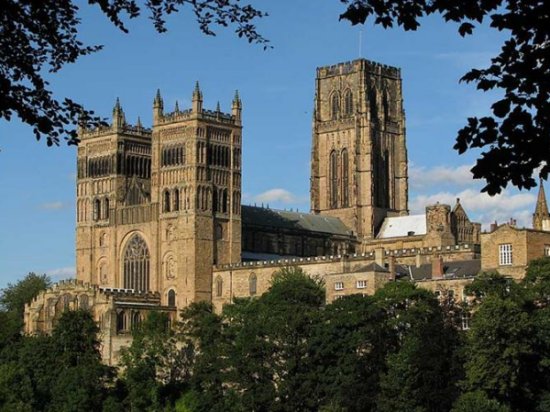

Christianity Inside Durham Cathedral

|

Built in 1093, Durham Cathedral has

been a place of pilgrimage and

worship for almost a millennium.

Originally built as a monastic

cathedral for a community of

Benedictine monks, Durham Cathedral

boasts some of the most intact

surviving monastic buildings in

England. The Cathedral holds an annual

Benedictine Week when there is an

opportunity to explore in more depth

the historical and living tradition of

St Benedict, focusing on its

expression at Durham Cathedral in the

past and present.

The Cathedral also served a political

and military function by reinforcing

the authority of the prince-bishops

over England’s northern border. The

Prince Bishops effectively ruled the

Diocese of Durham from 1080 until 1836

when the Palatinate of Durham was

abolished.

The Reformation brought the

dissolution of the Priory and its

monastic community. The monastery was

surrendered to the Crown in December

1539, thus ending hundreds of years of

monastic life at the Cathedral. In May

1541 the Cathedral was re-founded, the

last Prior became the first Dean, and

twelve former monks became the first

Canons.

|

|

(Pictured above the Choir Stalls)

In the Old Testament, craftsmen who were skilled in working with gold, silver, bronze, stone, wood, embroidery and weaving were given the responsibility of creating a beautiful place of worship (Exodus 35:30-35). Christianity welcomes the contribution of the arts in worship where they have a role in illuminating and teaching the Christian faith, in aiding our contemplation of God, and in provoking us to thought and new insights about God which words alone might not suggest.

The art in the Cathedral is not there for its own sake, as in an art gallery, but is part of the fabric of this holy place and is intended to help those who look at it to draw closer to God.

|

|

The Quire

The quire, and beyond it the sanctuary, were the heart of the medieval church. Here, in a space once entirely enclosed by the pulpitum, stalls and screens, the monks of the Cathedral Priory would gather seven times each day to sing the divine office. This offering of daily praise and prayer was known as the opus Dei, the work of God.

Around it the whole of monastic life was organised. In 1539 the monastery was dissolved by order of Henry VIII, one of the last foundations to be suppressed in England, and in 1541 the Cathedral was refounded as an Anglican institution.

The cycle of daily worship continued in the Reformed style familiar to us now as the services of morning and evening prayer in the Book a/Common Prayer of the Church of England. Apart from the Civil War (1649-1660) when the Cathedral was closed for worship, this rhythm has continued each day ever since, with the choir of boys and men now singing evensong six days each week during term-time together with Sunday morning matins and sung eucharist, the principal service of the week.

As was usual in a medieval church building, the Cathedral was constructed from east to west so that the high altar and the shrine of St Cuthbert could be installed as soon as possible and worship and pilgrimage could begin. The east end of the church down to the crossing was complete by 1104, although the quire

|

|

The Sanctuary

East of the quire lies the sanctuary. It houses the high altar, the principal focus of the church. Here the sacrament of the Eucharist (the Mass or Holy Communion) is celebrated, the bread and wine representing Christ's body and blood given for the world. It is the place of recognition and gift for the people of God, where the journey begun at the font reaches its culmination.

The sanctuary is marked out as this point of climax by the great stone reredos behind the altar. This, the Neville Screen, is one of the treasures of Durham Cathedral. It was largely the gift of John, Lord Neville whose tomb-chest is in the nave.

Completed in 1380 out of stone thought to have come from Caen in northern France, it would originally have been brightly painted, and statues of angels and saints would have stood in each of the 107 niches. All this was swept away in the years that followed the Reformation. (The alabaster figures, it is said, were buried by the monks before they could be destroyed; if so, their whereabouts remain one of the great mysteries of Durham.) The screen is still impressive today for the purity of its stone and the simplicity of its Gothic lines. On either side of the altar, incorporated into the screen, are the sedilia, stone seats for those assisting at services at the high altar.

The high altar itself is modern, but within it stands a modest 17th-century marble altar that is used during Holy Week, the annual celebration of the death of Jesus. The coloured patterned marble pavement in the quire and sanctuary is again the work of Scott, of a piece with his pulpit and screen at the crossing.

|

|

The portrayal of the Christian story in art in Durham Cathedral begins in the Galilee Chapel with the statue of the Annunciation by Josef Pyrz. The story of the annunciation, when the Angel Gabriel told Mary that God had chosen her to be the mother of his Son,

is found in the Gospel of St Luke (Luke 1:26- 38) and is one of the most popular scenes in Christian art.

Most artistic representations of the Annunciation show both Mary and Gabriel and portray a vivid range of emotions in both characters. But here in Durham, (pictured left) only Mary is portrayed and she stands serene, nearly life size and erect like one of the slender pillars.

This Mary, Star of the Sea (Stella Maris window pictured right) in the north-east corner of the Galilee Chapel complements the statue of Mary; both being particularly appropriate since the Cathedral is dedicated to Blessed Mary the Virgin and the Galilee Chapel was added as the Lady Chapel when women could not enter the main part of the

Cathedral.

The window relies on the use of symbolism and shows, on the right, Christ's ministry in Galilee represented by the Chi-Rho symbol for Christ, which is a monogram of the first two letters of his name in Greek.

The left-hand light represents Mary, symbolised by her crowned initial and by two flowers. The lily represents purity and the cyclamen, which has a red spot at the heart of the flower,

can be taken to express her sorrows.

The burning bush is from the story in Exodus where God called to Moses out of a burning bush that was not consumed by the fire and illustrates both God, who cannot be consumed, and Mary who bore Christ, without herself being destroyed by the fire of God's love. The descending dove is the Holy Spirit who

descended on Christ at his baptism and on Mary and the other disciples on the day of Pentecost.

|

|

The Galilee Chapel

Like the feretory, the Galilee holds a firm place in the affection of people across the North-East for the shrine it contains. A simple Latin inscription on a tomb-chest identifies its contents as the bones of the Venerable Bede. It is thanks to Bede's writings that we know so much about the Church in England in Saxon times, and in particular about St Cuthbert. Known as the 'father of English history',

The Venerable Bede was born around 672-673 and, aged seven, entered the monastery at Wearmouth. There, he was educated by the scholar and bishop, Benedict Biscop and later by Ceolfrith, with whom he moved to the new sister monastery at Jarrow, which was founded in 682. Bede and Ceolfrith were the only two survivors of a plague in 686, and maintained the monastic cycle of prayer.

Bede was ordained deacon in about 692 and priest in 702. He wrote his first book in 70l. He rarely left Jarrow but, drawing on Benedict Biscop's library of 300 to 500 books, he became the greatest scholar of his age. Bede was a teacher as well as a writer; he enjoyed music and was a good singer. His writings embraced science, astronomy, grammar, history, poetry, biblical studies, music and theology. He knew Greek and Hebrew. We are indebted to him for most of what we know about the other Northern Saints through An Ecclesiastical History of the English People which he completed in about 731. He also wrote two lives of Cuthbert.

Bede died on 26th May 735 while dictating his commentary on St John's Gospel. He had reached chapter 6 verse 9, the story of the feeding of the five thousand. When commemorating him each year in the Cathedral we stop the reading at that point with Andrew's question about the five loaves and two fish, "But what are these among so many people?" Bede's remains were brought to Durham in about 1020 by a monk who had taken them from the monastery at Jarrow and they are buried in the Galilee Chapel.

In 1970, words taken from Bede's Apocalypse were placed on the east wall of the Chapel (pictured above) in Latin and English in memory of Cyril Alington, Dean of the Cathedral from 1933-51, and his wife Hester. The designer was George Pace (1915-1975) and the letter-working was by metalworker Frank Roper (1914-2000).

Above the shrine burns an eternal flame, set in a polished brass lantern with a six-pointed star under the base of the glass. Tongues of flame rise from the upper rim, all under the umbrella of the Star of David. The underside of the Star of David has multi-faceted ribs derived from the architectural form of the arches in the Galilee Chapel. Hanging a perpetual light to designate a holy place is a long-established tradition in the Church; the light symbolises Christ, the Light of the world, and reminds us that we, shining as lights in this world, share the inheritance of the saints in light. The light also reflects Bede's words on the Alington memorial. The eternal flame was given by Rotary International to mark their centenary in 2005 and was designed by the Cathedral Architect, Christopher Downs.

|

|

The Venerable Bede Window

Alan Younger's Bede window in the north side of Galilee Chapel commemorates the 1300th anniversary of the birth of the Venerable Bede in 672/3. There is much detail within the window: look carefully and you will find images of Bede; Aidan on his horse; Bede's two teachers, Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrith; and the names 'Jarrow' and 'Wearmouth', the monasteries where Bede spent his life.

It is possible that Younger was influenced by Bishop Lightfoot's suggestion that the Celtic and Roman Churches were brought together in Bede - the left light focuses on the Irish Church with the Dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit, at the top, and the right, with the keys of St Peter at the top, on the Continental Roman Church. The central light focuses on Bede himself, showing him at his studies. Lilan Groves, one of the Cathedral Guides, thinks that the chalice in the left-hand light may represent Cuthbert who, Bede tells us, was

often moved to tears when celebrating the Eucharist.

Alan Younger (1933-2004) was committed to preserving the traditions and skills of stained glass work. His designs in numerous medieval churches, St Alban's Abbey and Westminster Abbey, are marked by bold use of colour and are strikingly modern. He cut and painted all the glass himself in his studio in his garden near Crystal Palace, letting details of the design emerge as he worked and rising to the challenges that were presented as the work progressed. He did much to promote the craft of stained glass in the twentieth century and was Vice President of the British Society of Master Glass Painters.

.

|

|

Lam'a Sabach'thani

Jesus was crucified on a cross, a horrific form of torture used by the Romans. This sculpture (pictured above left) shows Jesus' body arching away from the cross, perhaps in the agony of pain and the tragedy of abandonment, but his slightly raised head hints at the hope of resurrection. The sandstone base represents the hill of Calvary. At the foot of the cross (pictured above right) the representations of an axe head and a skull, items traditionally placed at the foot of crucifixes, represent the last judgement and the medieval legend that the cross of Jesus was placed on the grave of Adam, thus undoing the effects of Adam's sin which has led to human separation from God. Jesus suffered that same separation from God in his death and the title of the sculpture, Lam’a Sabach’thani, comes from the words cried loudly by Jesus just before he died on the cross, which are recorded in Aramaic in St Matthew's Gospel, "Eli, Eli, Lam' a Sabach'thani", "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Matthew 27:46).

This sculpture by the Russian Sculptor Kirill Sokolov (1930-2004) was donated to Durham Cathedral in 2006 by his widow, Dr Avril Pyman. It is made of wood, bone, iron and stone and was cast in bronze by Eden Jolly of Scottish Sculpture Workshops in 1997.

|

|

The Durham Light Infantry Chapel

The Regiment was formed in 1758 when the 2nd Battalion of the 23rd Regiment of Fusiliers was redesignated as the 68th Regiment of Foot. Its first engagement was raiding the French coast during the Seven Years War (1756-1763) to aid Britain’s ally Frederick the Great of Prussia. During 1764-1806 the Regiment was stationed 4 times in the West Indies, earning it the motto ‘Faithful’ for the St. Vincent Campaign during The Second Carib War (1795 - 1797). The greatest killer during this time was Yellow Fever, in one year over 700 men died.

A former officer of the Regiment, James Hackman, gained notoriety in 1779. He was hanged for murdering Martha Ray; the Opera singer and mistress of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, in a jealous rage after she spurned his affections.

In 1808 the 68th converted to Light Infantry, training with the 85th at Ashford, Kent under the tutelage of the master of light infantry training, Lt. Col. Franz Von Rothenburg. Light Infantry provide a skirmishing screen ahead of the main body of infantry in order to delay the enemy advance.

The Regiment moved to Spain and served during The Peninsula War (1808-1814) fighting at The Battle of Salamanca, The Battle of Vittoria, The Battle of Pyrenees and then Battle of Orthez. The Regiment was not engaged in any major actions for the next 40 years, primarily on garrison duties around the globe until it served during the Crimean War (1853-56).

In 1881 the 68th was amalgamated with the 106th Regiment of Foot (Bombay Light Infantry), which was formed in 1839 by the Honourable East India Company and served during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, to form The Durham Light Infantry. The newly formed Regiment went on to serve in India, Ireland, South Africa (1899- 1902) and the Middle East but took no part in the Boer War and then went on to serve during two World Wars.

In 1968, The Durham Light Infantry was amalgamated with the Somerset and Cornwall Light Infantry, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, and the King's Shropshire Light Infantry to form The Light Infantry Brigade. In 2007 another round of amalgamations meant the Light Infantry was merged with The Devonshire and Dorset Light Infantry, The Royal Gloucestershire, Berkshire and Wiltshire Light Infantry and The Royal Green Jackets to form The Rifles.

|

|

The Last Supper

Colin Wilbourn's Last Supper table was created in 1987 when he was Artist in Residence in the Cathedral. Educated at the University of Newcastle, he has worked since then in the North-East. Following his residency, he created a large outdoor sculpture, The Upper Room, which depicted the scene of Christ's Last Supper in the upper room of a house.

This complementary sculpture, in the Galilee Chapel, was mostly made from 500-year-old oak that was removed from the Cathedral bell tower during restoration work.

When closed, it shows a small table set with a platter of bread and a jug of wine but it opens out to provide a flat table surface and is used as the altar table each year during the Maundy Thursday Eucharist in the Cathedral Quire.

The story that it illustrates is that of the Last Supper which Jesus shared with his friends on the night before he was betrayed. This took place in an upper room at the beginning of the Jewish Passover celebrations. During the meal, Jesus took the bread, blessed and broke it and gave it to his disciples, telling them, "This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me". Then he took the cup of wine and said "This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood" (Luke 22:14-20). Through the centuries since then, in the Eucharist ('thanksgiving') which is at the heart of Christian worship, Christians have taken bread and wine, and followed Christ's example in blessing, breaking and sharing them. The Eucharist is a foretaste of the heavenly banquet in God's kingdom of justice and peace.

This work of art was purchased using bequests given in memory of a former Dean of Durham Cathedral, the Very Revd Peter Baelz - who did much to encourage the visual arts in the Cathedral - and a former Master of Grey College, Mr Victor Watts.

|

|

At the west end of the Nave, the south window (pictured above left) by Hugh Easton shows St Oswald, King of Northumbria, holding his sword aloft, echoing the cross beneath it which is the cross at Heavenfield where Oswald was killed fighting pagans.

The Heavenfield cross is surrounded by standing figures, one of whom has a similar pose to St Oswald. The implication is clear - Oswald's sword is as much a sign of his profound Christian faith as it is a sword for battle. It was also, as was the cross for Christ, the means of his death.

At the base of the window there is a memorial to Patrick Alington - the son of Cyril Alington who was Dean of Durham from 1933-51- who died serving as a Captain in the Grenadier Guards in 1943.

On the north side, (pictured above right) St Cuthbert, dressed as a bishop, is depicted in the

sea, surrounded by a halo of terns, puffins and kittiwakes, in reference to his residence on Inner Farne. This window was damaged in a gale on 13th January 1984 and was repaired by Mike Davies of Brandon Village in a similar style to the original.

Both windows were given by the Friends of Durham Cathedral in 1939 but their installation was delayed until 1945 and thus they are the first examples of post-war art in Durham Cathedral.

Hugh Easton (1906¬1965) is responsible for several windows in this Cathedral. The son of a doctor, he worked in Cambridge and London. His work often features substantial areas of undecorated glass that make the figures more prominent. This distinctive design approach can be seen in his St Cuthbert and St Oswald windows.

|

|

Mining has long been a part of the life of County Durham, and the association between the miners and the Cathedral is strong. Bishop Westcott, Bishop of Durham from 1889-1901, was known as the Miners' Bishop and his successor Bishop Moule went into the mines. Although the last pit closed in the 1990s, the annual Miners' Gala is still held in Durham and the Miners' Gala Service fills the Cathedral with mining communities bringing their new banners to be dedicated, accompanied by their brass bands.

The Miners' Memorial was created in 1947 as a symbol of this long association of Durham Cathedral with the mining industry. It looks old because it is made from wood from Cosin's seventeenth century organ screen. This part of the screen had been given in the early 19th century to the Pembertons who lived at Ramside Hall and they used it as a fireplace. When the Cathedral proposed a miners' memorial they gave it back, saying the Cathedral could have "their fireplace".

It reminds us of the human cost of mining because it serves as the memorial for miners who have lost their lives in pit accidents.

The memorial book lists the people killed in pit accidents. A miner's lamp hangs above the book, echoing Christ's words, "I am the light of the world" (John 8:12) and the opening to St John's Gospel, "The light shines in the darkness and the darkness did not overcome it" (John 1:5).

The inscription on the memorial, "Remember before God the Durham miners who have given their lives in the pits of this country and those who work in darkness and danger today" were set

to music and the anthem was first sung as an act of remembrance at the Miners' Gala Service in 2007.

|

|

The Nave

The nave reveals the ground-breaking character of this extraordinary building. It was here at Durham that for the first time in England masons solved the engineering problem of how to throw a stone vault safely across such a large space. The nave vault is entirely Norman work, completed in 1133. But the arches that spring from the great compound piers on either side to span the width of the nave are pointed, not round-headed like those of the arcades, the gallery and the clerestory which we associate with Norman architecture.

The pointed arch is a much more efficient load-bearing structure than the round-headed arch. Together, the pointed arches and the diagonal ribs that criss-cross the vault enabled the nave to be constructed entirely of stone. To span a width of 32 feet/l0 metres with a vault rising to 75 feet/23 metres was a pioneering achievement that paved the way for the emergence of the Gothic style in the next century.

The most important piece of furniture in the nave is the font (pictured above right), close to the main entrance. This is the place of Christian initiation, where children and adults are admitted into member¬ship of the Church through baptism. Traditionally, the font is placed near the door of the church as a symbol of entrance and belonging. Standing at the west end of the building,

|

|

In the fourth century, there was a flowering of theological study in Cappadocia, (part of modern Turkey), particularly associated with Basil the Great, his brother, Gregory of Nyssa, their sister Macrina, and Gregory Nazianzen (330-389). These theologians and church leaders were responsible for the development of the doctrine of the Trinity: that God is Three Persons in One God.

Gregory Nazianzen was, reluctantly, consecrated Bishop but eventually in 375 withdrew to a monastery. With the rise of the Arian heresy, Gregory emerged as one of the leading orthodox theologians of his day and was persuaded to become Bishop of Constantinople. However, church administration was not his real calling and again he wi thdrew, ending his life working as a theologian and writer, being remembered particularly for his contribution to Trinitarian theology through his writing about the Holy Spirit.

The Chapel in the North Transept is dedicated to St Gregory, hence the St Gregory Window (pictured above left). It includes a quotation, "Thy attuning teacheth the choir of the worlds to adore thee in musical silence" and a Greek quotation "to eternity". This echoes the words of God to Job that "the morning stars sang together and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy" when God began creating the world (Job 38:7).

The Millennium window (pictured above right) brings the history of the modern world into dialogue with the history of this region, especially St Cuthbert on whom the top half of the window focuses.

There are scenes from Holy Island where he lived - the coffin of the saint being taken from there when the threat of invasion by the Danes in 875 forced the remaining monks to flee, and of Chester-Le-Street, where his body rested for 107 years before being brought to Durham.

The lower half of the window illustrates contemporary life in the region, including glass-blowing, ship-building, chemicals, car manufacture and coal-mining: all linked to shipping, shown by the Tyne Bridge, and railways, shown by Stephenson's 1825 Locomotion engine which reminds us that railways are a gift of County Durham to the world, beginning just a few miles south of here.

|

|

A Pieta (Latin pietas, meaning pity) is a sculpture, painting or drawing of the dead Christ supported by the Virgin Mary. This is not derived from a biblical account, but we are told that Mary was present at the crucifixion and thus watched her son die the slow, cruel death that crucifixion brought about. This pieta expresses Mary's love and sorrow and reminds us of the cost of her "yes" to God all those years earlier and her faithful commitment to God despite the unjusified suffering of her son. This pieta, by Fenwick Lawson, ARCA, who lives close to the Cathedral, is non-traditional in that Jesus lies at Mary's feet rather than being supported by her.

Lawson made this Pieta (pictured above) from beech wood and brass (some of it from his wife's sewing machine) between 1974 and 1981. He aims to embody both death and resurrection. Death is shown through the brutalised crucified body in which the bruised, bent knees and the dismembered, unformed arm show the history of events. Resurrection and life are expressed through the lifting arm and the dynamic of the hand, stretched out to the mother, recalling Jesus' words from the cross, entrusting his mother to the care of his disciple, "Woman, behold your son", and, "Behold your mother"(John 19:26).

The unpolished brass, which is a vehicle for light and a metaphor for life, is meant to reinforce this and signifies the transfiguration of Christ earlier in his life - even in death, God's light is not extinguished. The splitting of the wood in the mother's face expresses the trauma of bereavement. She is both Mary, the mother of Jesus, and the universal mother who has contained

and given life, now expressing understanding and compassion at the death of her child. She represents all people who have stayed alongside others in their suffering. The outward gesture of her hand offers life, through sacrificial death. This is not the beautiful young Mary of the annunciation, but Mary harrowed by suffering who, nevertheless, sees the horror through to its end, not abandoning her son in his hour of need. Her presence at the cross is an example of discipleship and love that does not count the cost but is shaped by love for others. Mary knows that the only response to crucifixion is faithful lament and the ministry of presence which comforts her son and is a protest against the horror and injustice of the crucifixion.

The Pieta was displayed in this Cathedral in 1984 and was then placed in York Minster where it survived the fire in 1984. The Christ figure was under burning timber but the mother was saved by a wrought iron screen. They were both splattered with molten lead falling from the roof, which the sculptor sees as enhancing the meaning of this sculpture in a way that he could not have done himself.

|

|

The picture in the Chapel of the Nine Altars shows Queen Margaret (c1045-93) with her son (pictured above left) who became King David I of Scotland.

Known for her piety, Margaret was born in Hungary, was at the court of Edward the Confessor but in 1068 fled from the Norman court. She was shipwrecked off the Scottish coast, taken in by King Malcolm III and married him, abandoning her intended monastic vocation. She w pious, frequently giving her husband's money to beggars. Eventually she won over her husband, who joined her caring

for the poor, sometimes serving nearly 300 needy citizens in their great hall in Dunfermline. Margaret built monasteries and churches, including a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline.

Malcolm was present when the foundations of Durham Cathedral were laid in August 1093 and Margaret may have attended the ceremony but her confessor, Prior Turgot of Durham, records that she was so ill that she could scarcely get out of her bed. Malcolm, Margaret and eight of their children appear in the Durham Liber Vitae the book of donors to the Cathedral.

Malcolm and their oldest son, Edward, were killed in battle at Alnwick fighting King William II of England. Margaret heard the news on 16th November 1093; she died while reciting the communion prayer, supposedly of a broken heart. She was canonised in 1249.

The altar frontal (pictured above right)suggests a jewelled and gilded book cover, the gold clasp of which is enriched with jewels and opens to reveal a simple black cross with a heart of pearls at the centre. This alludes to Margaret's greatest treasure, a relic of the true Cross, but there is also a double symbolism to this heart - both the love of Malcolm for Margaret and the concept of the heart as the source of understanding, love, courage, devotion and joy; all of which were exemplified in Queen Margaret.

The location of the Margaret Altar at the east end of the South Quire Aisle was deliberate, picking up on a reference in the Rites of Durham (1593) that" At the east end of the south alley ... there was a most fair rood ... the black rood of Scotland wrought in silver and having crowns of gold." The altar was dedicated to St Margaret of Scotland in 2005 as part of a desire to make women more visible in the Cathedral. Margaret challenges us to steely commitment that can endure the hardships of

a turbulent life.

|

|

Hild was a seventh century Abbess of Whitby and a contemporary of Aidan and Cuthbert. Born into the royal family, she abandoned the life of the court and entered monastic life. Eventually she was appointed Abbess of Hartlepool by Bishop Aidan. Later she founded the double abbey of monks and nuns at Whitby and was known for her prudence and good sense: kings and other leaders sought her advice. The Synod of Whitby was held at her monastery in 663 when divisive issues between the Celtic and Roman Christian traditions were resolved, most significantly that of the date of Easter which was celebrated at different times in the two traditions.

Many of her monks became bishops or scholars of Scripture She is also remembered for encouraging a shepherd boy, Caedmon, to become the first English-language poet. Hild, who was universally known as "mother", died in 680 and is remembered as one of the most significant women in the English church, which welcomed the ministry of women.

The altar frontal (pictured above left) depicts the sea and seabirds, both regularly associated with St Hild due to her years as abbess at Hartlepool and at Whitby which are sited on promontories overlooking the sea. The cloth represents the sea and is worked in various shot blue silks to suggest the tides and the play of light on the surface of the water. The technique used is traditional Durham quilting where the linear elements are drawn into running stitch. A natural white cloth over the blue cloth represents the wings of sea birds flying which, tradition tells us, dipped their wings in salute to Hild as they flew over the abbey at Whitby. The wings are symbolic of divine mission and follow the shapes of birds in Celtic art. They may suggest a Goose which has long been associated with providence and vigilance and, in the tradition of the Northern saints, can also represent the Wild Goose, the Holy Spirit. Others may see in the wings a dove - symbolising purity, peace and the Holy Spirit who descended on Jesus in the form of a dove.

The Icon of St Hild (pictured above right) is unusual in showing thirteen scenes from the life of a western saint in the art of the eastern church; it is contemporary yet created in the historical tradition of icons. She is shown building the monastery at Whitby; at the Synod held there; offering charity to the poor; encouraging Caedmon; and counselling kings and bishops who sought and heeded her advice. The icon was written (icons are written, not painted) by Edith Reytiens from Dumfries. She trained with Tom Denny who created the Transfiguration window.

This icon was commissioned by the Community of Women and Men in the Church and the Cathedral Chapter contributed to it. Like the Margaret Altar, the altar dedicated to Hild is part of the Cathedral's

|

|

The Shrine of St Cuthbert

Behind the high altar, reached by steps from the quire aisles, lies the Shrine of St Cuthbert. He is buried beneath a simple stone slab that bears his name in Latin: CVTHBERTVS

One of England's most remarkable men Cuthbert, a Northumbrian, was born in about 634.

A guardian of sheep in the Scottish border hill country, he entered the monastery at Melrose, later moving to the 'holy island' of Lindisfarne, first as prior to the community there, then in 685 as bishop. It was here that the Irish monk Aidan (died 651) had established a monastery as the headquarters of his mission to reconvert Northumbria to Christianity at the invitation of King Oswald (c. 605-642).

Cuthbert's holiness, learning and love of nature, his care for people and the fervour of his preaching were already legendary in his lifetime. He had established a hermitage on the island of Inner Farne where he died in 687. He was buried on Lindisfarne. Eleven years later his body was disinterred and found to be

undecayed, whereupon his shrine was set up on Lindisfarne. This was Northumbria's golden age, and its cultural and intellectual achievement is demonstrated in the Lindisfarne Gospels, written there early in the 8th century in honour of God and St Cuthbert'.

By the 9th century, Viking raids drove the community of St Cuthbert' to seek a new, more secure, home. The community, carrying the relics of Cuthbert and the Lindisfarne Gospels, started a long journey round the north of England. They came to Chester-le-Street in 883 where they rested for over a century. In 995, having stayed briefly at Ripon, they arrived in Durham. Legend says that as they approached the peninsula, the cart bearing the coffin stuck fast in the ground. Some women were overheard talking about a lost cow. 'Dun Holm' was mentioned as the place where the animal would be found. This was taken as a sign from Cuthbert, so the coffin was duly brought on to the peninsula where it has remained ever since.

The community's first church on the site lasted less than 100 years. In 1083 a Benedictine convent was founded in place of the Saxon community, and a decade later the Norman Cathedral was begun as a more splendid house for the shrine. Cuthbert's relics were installed in their present position in 1104. Durham rapidly became the foremost pilgrimage destination in England, and one of the wealthiest. Only with the martyrdom of Thomas Becket in 1170 did Canterbury eclipse it, although Durham's energetic promotion of the pilgrimage ensured that the shrine continued to attract pilgrims throughout the Middle Ages.

In late 1537, the King's commissioners came to Durham to dismantle the shrine. It was stripped of its gold, silver and jewels and levelled to the ground. When Cuthbert's coffin was uncovered, they found not dust and bones but a body in priestly vestments 'fresh, safe and not consumed'. As a result it was left alone and re-interred. The grave has twice been opened up since then, in 1827 and 1899. The precious artefacts from Cuthbert's time removed in 1827 are now on display in the Treasures of St Cuthbert exhibition. The stark black slab that bears his name is, perhaps, as eloquent a tribute to the simple prior, bishop and hermit of Lindisfarne as his elaborately jewelled shrine had once been.

In 2005, St Cuthbert's name was reinstated in the legal dedication of the cathedral from which it had been removed in the 16th century. It is now dedicated to 'Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert'.

|

|

There is so much more to see inside our wonderful Durham Cathedral, arguably the greatest building in our Region if not the Country.

|

|

|

|

|

|