|

|

The Bygone Days Of Gateshead Metropolitan Borough

|

The Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead

covers a large area. To the north the

boundary is the River Tyne and the

City of Newcastle, to the south

Kibblesworth and Birtley. To the east

are Felling, Heworth, Bill Quay and

Wardley, to the west Whickham,

Swalwell, Blaydon, Winlaton, Ryton,

Crawcrook and Rowlands Gill.

Once described by Samuel Johnson as 'a

dirty lane leading to Newcastle' and

unfortunately such an image has long

persisted. It is often assumed by

visitors to the area that Gateshead is

an offshoot to Newcastle, created by

Newcastle spreading south of the

river. This is not the case. Gateshead

has long been an industrial and urban

centre in its own right, with a proud

history, and a rich heritage.

Gateshead is first mentioned in Bede's

History of the English Church and

People and the first settlements lay

along the river Tyne close to where

the Tyne and Swing Bridges now stand.

By 1344 coal-mining had become a

significant feature of the area, and

wharves were constructed along the

river at Pipewellgate to transport

the 'black gold'. Pictured above, Pipewellgate in 1898 when Brett's premises housed a glassworks. The sector of riverside land known as Pipewellgate was for many years the main centre of Gateshead. It ran from Redheugh to the old Tyne Bridge (now the Swing Bridge). The Ordnance Survey map of 1858 shows a collection of noxious industries including chemical works situated within this area. 'Pipe' in the name may be a reference to pipes carrying water.

Gateshead continued

to develop in the 1600s but during and

after the Civil War the town began to

decline, as it was no longer

economical to mine the deeper coal

seams further inland that were now all

that remained of its coal riches.

It was not until the mid 1700S that

technological advances meant that such

reserves could be exploited, and

Gateshead once more began to prosper.

Coal mining led to ship building which

in turn led to rope-making; other

important industries consisted of

mills, quarries, potteries, ironworks,

brickworks and chemical works.

The cumulative effect of this

industrial development was to create a

dramatic increase in the population,

and by the 1800s citizens were packed

into poor insanitary housing that bred

a host of social and health problems;

outbreaks of cholera for example being

distressingly common.

By the 1860s, more land to the south

and east became available for public

housing and so Gateshead gradually

spread from its original heart.

Communities were established at Low

Fell and Sheriff Hill and Saltwell

Park was created for public benefit in

1877. Imposing residences were

constructed for the well-to-do

industrialists who had triggered

Gateshead's expansion, and the Housing

Act of 1909 led to the clearance of

some of the overcrowded slum areas.

After the First World War other areas of poor housing were demolished and new

communities established in Carr Hill,

Wrekenton, Deckham and Lobley Hill,

with the construction of the Tyne

Bridge in the 1920S the slums of

Pipewellgate (pictured above) and Bottle Bank were finally cleared.

From the 1920S Gateshead began a slow

industrial decline as the traditional

heavy industries began to fail, and an

attempt was made to improve matters

with the creation of the Team Valley

Trading Estate in the 1930s. During

the 1950s, attempts to solve the

chronic housing shortage led to the

construction of tower blocks,

and 'village' concepts, though they

generally led to a collapse of the

community spirit and greater social

problems.

During the 1960s and 1970S the old

heart of Gateshead was largely cleared

to provide relief roads, flyovers and

bypasses that seemed only to exist to

enable people to reach Newcastle with

greater ease, leaving Gateshead even

more isolated and resentful.

From such bad times Gateshead has

experienced a slow regeneration, not

only of its landscape but also of its

pride. The building of the Metro

Centre in 1986 and the National Garden

Festival in 1990 kick-started further

civic and social developments and more

recent high-profile developments along

the quayside such as the Millennium

Bridge, the Baltic and the Sage and

the sculpture the 'Angel of the North'

have further led to a rise in civic

pride.

The folk of Gateshead have endured

years of boom and bust and their town

has undergone many dramatic

transformations. Parts of Gateshead

have experienced significant

regeneration, some elements remain

virtually unchanged. It is also clear

that some of the regeneration may have

been in the 'name of progress' but it

has not exactly led to an improvement

in the environment.

|

|

The Great Fire at Gateshead

On 6th October, 1854 Very early on that Thursday morning, in fact just after midnight, a fire began at Hillgate, a street running parallel to the river bank. The worsted factory belonging to Messrs.J.Wilson and Sons contained quite a lot of heavy machinery resting on wooden floors and it took less than one hour for the factory to be completely gutted. But by that time the fire had spread to the next building going east towards the sea, a six-storied building some eighty feet long and twenty feet wide known as Bertram's Warehouse. Originally it had been used to store the goods of the firm, Bertram and Spencer, but had, for quite some time, been used as a general storehouse for all sorts of goods belonging to various merchants from both Gateshead and Newcastle.

Consequently no one could exactly identify its contents but it was said to contain some two hundred tons of iron, eight hundred of lead, one hundred and seventy of manganese, together with various quantities of nitrate of soda, alum, arsenic, copperas, salt, naptha, guano and a massive three thousand tons of brimstone.

Gateshead residents were quite aware of the fact that a huge amount of combustible material was stored there, so excitement mounted as onlookers collected to await events.

Fire brigades from both Gateshead and Newcastle were already at the scene of the fire, as was a military detachment of fifty men with their machines from Newcastle Barracks. Streams of vivid blue flames from the sulphur made a spectacular entertainment for hundreds of onlookers on both banks of the Tyne, as well as on the bridges themselves. At that point the fire brigades were very confident that the fire would be contained within the two buildings. It seemed to have been forgotten that much of Hillgate had been burnt down that same month four years earlier, and had been substantially rebuilt.

Besides the spectators, a great number of people were either fighting the fire or trying to save valuable possessions from neighbouring houses threatened by the fire. Then quite suddenly about a quarter past three, a huge explosion took place. An eye witness described it in these words.

The air was rent as with voices of many thunders, and filled as with the spume of a volcano. Massive walls crumbled into heaps, blocks of houses tumbled into ruins, windows shattered from their frames far and near, and a shower of burning timber and crashing stones rained terror, destruction and death on every side.

Alarm spread on both sides of the river as a spectacular fire turned into a major disaster. Keels moored in the Tyne were blown onto the banks, the massive iron High Level Bridge quivered on its pillars, burning piles of brimstone with bricks, stones, wood and metal of every kind were thrown around to fall on onlookers before they could even move away from their viewpoint. Those not killed outright were maimed, bruised, battered and wounded, many seriously. Firemen were crushed where they stood in the narrow roadway that was Hillgate when rubbish fell from the sky by the ton. In many cases death was instantaneous. Others more fortunate rushed naked and shrieking into the street, running they knew not where.

A writer was later to pen the words, a battlefield could not have yielded a more terrible tragedy. Limbs were torn away, bones fractured, lumps of wood forced into the human body, hot stones buried in the flesh, burning sulphur wrapped around unconscious victims and every conceivable injury inflicted on man, woman and child. Crushed and scorched bodies of the dead were taken to the police station in Gateshead for identification. The wounded were taken to Newcastle Infirmary and the Gateshead Dispensary .

The immense power of the explosion could be gauged by the fact that it burrowed into solid ground and undermined huge blocks of granite which formed tramways for the carts in Hillgate and it cast these huge stones hIgh above St Mary's Church some three hundred yards away to destroy houses in streets even further afield. These huge blocks, some weighing four or five hundredweight, landed in Oakwellgate, five hundreds yards away, while others cleared the river to destroy houses in Grey Street and Pilgrim Street in Newcastle. Fires began on the Newcastle Quayside and many of the numerous chares (narrow streets) were destroyed. Because the Newcastle fire engines were engaged across the river and the Gateshead ones had been destroyed by explosion and fire, engines were sent from both Shields at the mouth of the river Sunderland and Durham from the, south, Morpeth and Berwick from the north and Hexham from the west. By dawn the destruction was evident and the flames still unsubdued. By the end of the day the fires on both sides of the river had burnt themselves out, leaving in their wake undescribable destruction. Many of the dead, so badly burnt, were unrecognisable, identified in some cases only by their signet rings, keys, a cigar case and, in the case of one of the firemen, by the nozzle of the engine pipe embedded in his bones. It had been an horrific forty-eight hours.

The inquest was adjourned several times and eventually closed on 2nd November. The cause of the explosion remained a mystery although it was generally agreed that no explosives had been illegally stored in the warehouse. Various causes were claimed, sulphur and nitre exploded in reaction to the water poured on them, a mixture of gases from the various chemicals caused them to explode. The inquest jury returned a verdict that the death of Thomas Scott and others occasioned by the accidental explosion of a quantity of nitrate of soda and sulphur. The immediate cause of the explosion was a fire in the worsted mill but in what way the two substances which caused the explosion, acted or re-acted, chemically or mechanically, we are unable to decide. And it was left only to rebuild Hillgate for the second time in less than five years, while caring for the permanently injured and mourning for the dead.

|

|

The Last Cutty Factory

Not far from the scene of the Great Fire of Gateshead is High Street (pictured above) with its supermarkets, office blocks, departmental stores and car parks, a far cry from days long ago, when one of the strangest factories in a narrow street off High Street was nearing its end.

Nowadays one passes over the Tyne Bridge from Newcastle on the way south and before you know it you are on a roadway on stilts over the top of it and it is gone forever. Time was when in order to do the same journey you had to travel up the High Street, and hard lines if you were in a hurry. As your car crawled up the steep street inch by inch in a near traffic jam you had ample time to look around you. Even so, I doubt if you would have noticed King William Street going off the High Street.

Even if, some seventy years ago, you had walked up High Street you would probably not have noticed it then, which, indeed, would have been a great pity. For if you had strolled through the narrow archway at the top of a flight of stairs you would have actually been in King William Street. So what was so remarkable about King William Street those many years ago. Well in that street the very last cutty factory in the country was about to close down. And what, I know you are dying to ask, is a cutty factory? It is said that silly questions get silly answers. A cutty factory is a place where cutties are made. And if you are now going to ask what a cutty is, then you are not a senior citizen of Geordieland.

Long before the days when cigarettes and briar pipes were popular, one had a smoke from a cutty ... yes, now you have it, a clay pipe. However, if you lived high up the social scale you smoked a churchwarden. In between the cutty and the churchwarden were many other varieties of clay pipes.

If you had spoken to the factory owner, Mr Stonehouse, he would have told you how, in the 1880s he was an apprentice in a Midlands factory where over two hundred men were employed making clay pipes. The demand was so great that this factory was only one of many throughout the country. So it was that Mr Stonehouse moved from the Midlands and set up his own factory in King William Street in Gateshead. And let us go back in time and take a look into his dark, damp and unaired factory, five or six rooms in a street mainly consisting of homes in a narrow alleyway with the rather grand name, which was, I regret to say, the only grand thing about the street.

Push open the door and gingerly walk into the room for its dim light is little help to safe progress. Disappearing into the darkness in front of you is a flight of stairs. Go through the door to your right and you will see pile upon pile of bricks of clay, pipe-clay, hard as stone and just arrived from far off Cornwall. The bricks must first be moistened, 'pug milled' and 'tempered' before they can be made into the exact shape of the pipe. In racks around the room you will see thousands of these clays ready to be baked in the big kiln in the room next door. In this kiln the bricks are fired for twelve hours to make them capable of withstanding the heat of burning tobacco.

Across the passageway in the room on the left is the pug mill where the moistened clay is churned by machine until it is in the exact state to be made into the pipes themselves. This was a far cry from the days before the advent of the machine, when the clay was placed on a bench and pounded with an iron bar in a long hard operation. Out into the passageway again and gingerly mount the stairs for the treads are now none too safe, as it will not be long now before it is finally vacated and demolished. Push open the door on the left and you will find yourself in a small workshop that looks as if it has been there for centuries. Here Mr Stonehouse, his wife and an assistant sit at their benches. In front of them are partly formed clays looking rather like a bunch of bananas. They have already been rolled into this shape by a rather fascinating process. Try placing a piece of clay in each hand and roll them quickly into the shape of two bananas at the same time, not as easy to do as it at first appears in writing. These rough shapes are to go into the moulds, of which some thirty or forty stand ready on the shelves. All are different shapes and sizes, some even now out of fashion and never used. All have names. There are Niggar Heads, Rustics, Ladies Heads, Dukes, Coun¬tesses, Buffalo Heads and many more besides, each with their own unique shape.

Each is made of steel in two parts, each part being used to mould half of the pipe lengthwise. Watch carefully as Mr Stonehouse places into one of these moulds a rough shape of clay. A press is brought down on top of the mould. The same procedure takes place with the other half, and so we have one clay pipe, or nearly so.

All that is now required is the hole in the middle. Now how do you put a hole in the middle of a clay pipe, especially one like the Churchwarden which was about twenty-four inches long, with no machinery to help with accuracy? Again watch Mr Stonehouse carefully. He has a long steel rod in his right hand which he pushes through the middle, or appears to do so. But this he tells us would just be disaster. In fact he holds the rod quite still and pulls the pipe stem, damp and wiggly, onto the rod, rather like a lady pulling a silk stocking onto her leg. And when the clay is dried and the mould is removed, all that remains is to trim off the rough edges left by the mould and tip the pipe, that is putting the little red colour¬ing on the end of the stem. Some are even tipped in black for use at funerals. And that is it.

If you are careful not to drop it, the cutty will give you years of use, and the smoking of tobacco will be far better with cutty than with a new-fangled briar.

But the factory has long since been pulled down, and King William Street as well. As the years have passed shops have risen on the cutty factory's site, have in turn been pulled down, and other establishments have occupied newer premises. And the cutties? The clay pipes? They are no longer popular with most pipe smokers but you can still buy them if you know where the right shop is in Gateshead.

|

|

The Brandlings of Felling Hall

A few yards from the old Brandling Station (pictured above right) across the road to the Mulberry Public House and the adjacent housing estate. Centuries ago this area was the beautiful grounds of a beautiful house stretching south towards the River Tyne.

So what is the connection between Brandling Station and the Mulberry? The answer to the question is a third building which is no longer there, Felling Hall (pictured above, less than opulent).

Felling Hall stood between the present railway lines and the River Tyne. Practically all the land in this area belonged, in the middle of the sixteenth century, to the hall's owner, Sir Robert Brandling. He was the forefather of the Brandlings of later years, who owned the railway which transported their coal from their mines down to the staiths on the River Tyne for shipment to London. Felling Hall continued to be the home of the Brandling family for a further two hundred years.

In the year 1760 Charles Brandling felt that the hall, to say the least, was a little past its best for such an important family. In any case he had taken a fancy to live in the fashionable district of Gosforth across the river in Newcastle, a district that had not yet been ravished by the demands of industry. So he had himself built a lovely mansion in what we know now as Gosforth Park.

After the Brandling family had moved into their new stately home, Felling Hall rapidly deteriorated. Bit by bit the walls began to crumble. The once lovely gardens became weed-ridden and full of everyone's rubbish. The weather and the vandals yes, they were there in those days as well, took their toll until only one part of the hall was of any use at all. It was converted for a far different use and called the Mulberry Inn, so named because one of the Stuart kings on a visit to Felling Hall planted a mulberry tree in the grounds.

This original Mulberry Inn was demolished in the early 1900s and the present Mulberry Inn was later built on a site quite close to the original. Parts of the old Felling Hall were used to build some of the houses that were built around the Mulberry Inn. A door here, a window there, a few stones here and there were used, not that anyone ever noticed or even cared that a little bit of history was being built into their houses. Even in 1930 one part of Felling Hall still remained. Well, not actually the hall itself, but the summer house which Charles Brandling had built shortly before he moved away from the estate to Gosforth. It stood to the north of the hall in the middle of some beautiful woods. It even remained there when the trees were torn from the ground to make way for the 'modern' housing estate. It still stood when the new school was built, even though the grass around the summer house was concreted over for use as a children's playground. The locals nicknamed it 'Brandling Tower'.

But even it could not go on forever and nothing now remains to remind us of one of the great stately homes of the area. A little green does still remain where the hall stood close to those 'modern' houses of Easten Gardens, now not so modern. The new school, referred to as the Low Board School, was pulled down to be replaced by the modern Brandling County Primary School, retaining the famous name at least. The new Mulberry Inn still stands. The tree is not to be seen anywhere. The inn serves the residents of the housing around it as did the old one.

But what is left to remind us of Felling Hall and the Brandling family, who were greatly respected in their time by the people of Felling. Not a lot,there is the Brandling Railway Station and the family crest nearly worn off by the weather, no one could really tell about its significance to Felling, although the front of the building does now display a plaque explaining its original use. The officials of Felling Urban District Council had ensured the Brandling name would go on, when they were far sighted enough to adopt the burning brand of the family as their official crest. They were not to know that about two hundred years after the family moved out of Felling, they themselves would be swallowed up by a bigger authority in the name of progress.

There are a few streets, Brandling Court, Brandling Place and Brandling Lane, while, practically on the site of the Felling Hall Estate is the Brandling Hall Community Centre. Strange then, that around the Gosforth area we have Brandling House in Gosforth Park, two Brandling Arms and a Brandling Villa, all three being thriving public houses. And there is Brandling Village itself, a small area practically lost in its larger Gosforth neighbourhood. There should be a moral somewhere.

|

|

A Factory Before Its Time

(pictured above left, the original entrance to the factory, above right, the original factory))

Close to which is the area of Swalwell and Whickham. On Market Lane there is a public house called the Crowley Hotel, whilst close by is Crowley Road with Crowley Avenue a little further away. A mile or so onward near to Winlaton is Crowley Gardens, all connected by name to a factory before its time.

Crowley's Crew may sound like something taking part in the Head of the River Races on an August Bank Holiday Monday, or even in the River Tyne Races, part of the National Garden Festival in Gateshead. Crowley's Crew were employees of a factory that was two hundred and fifty years before its time.

Long ago one of the most important industries south of the River Tyne was iron and steel, and the most important works belonged to Messrs. Crowley, Millington and Company at both Winlaton and Swalwell The founder of the firm, Ambrose Crowley, first began work as an anvil maker in the Midlands town of Dudley in the county of Staffordshire. There he made enough money to encourage him to set up his own factory, so he travelled north to Sunderland where he set up a factory making iron goods, mainly household utensils. But his factory on the banks of the River Wear was never the success he imagined it would have been, so about the year 1690 he closed it down.

He travelled north to Winlaton and there he set up another factory. His advert in a local paper stated that: at his works in Winlaton any good workman who can make the following goods shall have constant employment and their wages every week punctually paid, namely, augers, bedscrews, box and sad irons, chains, edge tools, files hammers, hinges, locks, nails, patten ring and almost every other sort of Smith's Ware.

The confidence in himself was to be fully justified for when Sir Ambrose Crowley died in London in 1713 he left £200,000, a number of valuable estates and a factory which, I am certain, was well ahead of its time. What made this works so remarkable at the time was, not the products made there, but the way in which Ambrose Crowley organised his work force and the good it did for the inhabitants of Winlaton. In the course of time he turned a few deserted cottages into a thriving town. He turned a factory into a community. He placed the workforce of his factory way ahead of any other workmen in comfort, in education and in intelligence. Everyone at the works, be they workmen or management, was governed by a strict set of rules, which bound all the employees together with common family ties. Every man employed at the factory from the humblest employee to the boss himself was registered.

Not only was a record kept of his name and address, but his age, height, weight, complexion, place of birth, details of parents and numerous unusual statistics like hobbies, interests and even whether or not he smoked a pipe, cigarettes or not at all, were all recorded. Details were also kept of the unusual events that took place during the life of the firm's employees. So it was that we learned that a certain employee, Anne Partridge of Dudley, got into debt and ran away from home and work. Today, no doubt trades unions would be up in arms, complaining of the intrusion into the private lives of employees, and the Council of Civil Liberties would have had Ambrose up in court. All correspondence to and from the firm was dealt with by a Committee of Survey, who had a most unusual way of dating its correspondence. They did not use the normal year calendar, but instead everything was based on the number of weeks the firm had been in existence, number one being the week the factory opened. So the last letters sent out by this amazing firm were 'dated' week 9,234, giving the factory a life of over 177 years which, in fact, is about five years less than the closing and opening dates given in other records.

Next to this Committee of Survey was a second unusual one. It was the firm's council, made up of all members of the Survey Committee, plus the cashier, the warekeeper and the iron keeper. This committee was an exceptionally powerful one, as it dealt with both criminal and civil matters. Any employee guilty of bad workmanship was brought before it. So were disputes both inside and outside the factory, if they concerned employees of the firm. It settled any arguments about debts of employees and was even empowered to recover debts of one employee to another. It disciplined an employee breaking factory laws, especially in matters of safety. In the event of anything having to be settled by public courts, it secured legal rights cheaply for employees, and in some extreme cases paid all fees outright. With very rare exceptions, orders made by the council and penalties issued by them were very effective.

So it was that the Council became better known by the nickname of 'Crowley's Court'. Perhaps modern workmen might dispute the right of such a court to have such massive powers, but the employees themselves, from the lowest to the highest, had the greatest of trust in the strict fairness of this court. But not only did the company deal with all legal matters, but also with social problems. Ample provision was made for those who were sick. An amount of ninepence in the pound, just under 4% on average, was taken from all employees' wages and the revenue used to feed, house and clothe the old and permanently disabled, and to provide an allowance each week for all those unable to work through illness. And all this two and a half centuries before anyone ever thought of the National Health Service, Superannuation or the Old Age Pension. Incidentally, the pensioners were known as Crowley's Poor and wore a badge on their left arm which had the words moulded on it, not one of Crowley's better ideas, I would suggest.

Then there was Crowley's School, where the children of all employees were superbly educated. The schoolteacher was paid out of the wages of the employees, who weekly paid 2 1/2d, which amount also paid for the chaplain, for the schoolroom was used as a church on Sundays. The first chaplain of the factory was listed as Revd Edward Lodge, who later became the headmaster of the Royal Grammar School in Newcastle. The nearby Ryton Church set aside the gallery for the exclusive use of the workmen of the factory, an arrangement made with the church authorities by the factory council. In 1819 the factory opened a library in Winlaton for the exclusive use of employees and their families, starting with a huge collection of 3,000 books. Sir Ambrose Crowley is said to have introduced freemasonry to the north of England, which is rather doubtful. Nevertheless he did form the first factory branch in the country.

Such then was Crowley's Factory, surely the forerunner of any worker participation industry in the country. It was truly a factory before its time, well before its time. Ambrose Crowley introduced so much that was new to industry, so much that was appreciated by all his employees, and so much that was socially good. His employees were top of the world, the envy of every other workman for miles around. But then things began to go wrong.

Crowley's Crew, as the employees became known throughout the area, became a law unto themselves, the terror of Tyneside, perhaps another first, the first 'bovver boys'. If they thought something was wrong they considered themselves above the law and perfectly entitled to put matters right without recourse to the law.

For example, on one occasion they considered that food being sold in Newcastle was far too dear. So they marched in a body into town, took over the market carts, sold all the goods to the public at what they considered reasonable prices, and then, when all the goods had been sold, handed the money they had collected and the carts back again to their owners. The local constabulary stood by and did nothing.

Many other examples of the attitudes of Crowley's Crew were often quoted.

It goes probably without saying that they were very politically minded, belonging to the Newcastle Radicals and could often be seen sporting

their green and white favours, like modern soccer supporters. After one rally on 11th October, 1819,

the Mayor of Newcastle wrote to the Home Secretary saying; It is impossible to contemplate the meeting of the 11th inst. without awe, more especially if my information is correct. Seven thousand of them were prepared with arms concealed to resist the civil powers. These men came from a village three miles from town, and there is strong reason to believe that the arms they used were manufactured there. He was not wrong, for the men did make an assortment of weapons there and were quite prepared, if necessary, to use their home-made articles to assist the election of the popular candidate at voting time. Maybe, in this unsavoury side of the factory, they were also well ahead of their time.

After reaching great heights, Crowley's firm went rapidly downhill, eventually closing in 1872. But was it a factory before its time? with its Crowley's Court, Crowley's School, Crowley's Church, Crowley's Poor, Crowley's Superannuation Fund, Crowley's Unemployment Benefit, Crowley's Old Age Pension, Crowley's Library and Crowley's Crew, perhaps it was. Indeed no, it most certainly was.

But today, well over one hundred years after the factory of Sir Ambrose Crowley closed and over two hundred and fifty years after his death, who, in the area of Blaydon, Winlaton or Swalwell knows about Crowley's Crew or even about the name itself. The frequenters of a certain hostelry and the residents of certain streets will certainly know the name well, of course, but what about the stories behind the name, Crowley, who did so much, has it seems been forgotten. Maybe, now, the fault has been rectified.

|

|

Saltwell Park, is the most beautiful of all the North East's public parks, the vast area of which the park is just a part was originally known as Saltwellside and was owned by the Ravensworth family, whose wealth was built mainly on the coal mining industry.

A succession of owners followed, led by Robert Brigham and the Hedworths of Harraton, who had a large mansion as their residence towards the end of the Elizabethan era. The Hedworths

sold it to William Hall, whose son, Sir Alexander Hedworth, passed it on to his brother. And so the selling and buying went on until eventually the land began to be parcelled off in lots.

Each purchaser had his own mansion on these villa sites, the four main ones being Saltwell Hall, Saltwell Towers (pictured above right), Saltwell Cottage and Ferne-Dene House. Even so the various sites continued to have a variety of owners. Saltwell Park was owned in the mid-nineteenth century by a William Henry Lambton, who, in 1853, sold the estate to William Wailes, who was to be the very last private owner of the land.

He was a prominent artist in stained glass and it was he who built the house on the land. The whole of the northern part of the estate was entirely fields, while the southern portion below and around the house was laid out as gardens. As Mr Wailes became older it was necessary to sell the estate, which was bought in 1876 by the Gateshead Corporation for £32,000. Mr Wailes, however, retained the right to live in the house until he died, his death taking place in 1881 at the age of 72 years. After his death the house was occupied by Mr J. A. D. Shipley, who is remembered in Gateshead because of the magnificent Shipley Art Gallery in the town.

The Gateshead Corporation began to develop the fifty-two acre site shortly after its purchase by making the north part of the estate into attractive grounds rather than the original fields. The first of three bowling greens was laid out in 1878, the other two following in 1887 and 1900. In 1880 a four and a half acre lake was developed, in the centre of which was built an island, onto which a bandstand was placed in 1907. An aviary was built close to the flower garden and maze, which Wailes had himself built before his death. The initial re-develop¬ment of the estate having being completed, the park was opened in the June of 1876. Development of the park has continued ever since, and yet in much of it one can easily see those first steps.

Saltwell Park is a quiet oasis amongst the busy streets which surround it on all sides, noisy with the constant hum of traffic. The southern part is still the garden of the estate, attractively and beautifully laid out with lawns and flower beds close to the Dene with its small but pleasant waterfall splashing playfully down towards its southern boundary. The centrepieces of the park are the wonderful mansion, Saltwell Towers and the lake.

So the whole of this southern area is one of history, plus modern beauty in the form of lovely lawns, flower beds, shrubs and trees. On the other hand the northern part in the main is much as it was in days gone by, a wide grassy space with the lake more or less as it was. Hired rowing boats now move amongst the swans, but perhaps they did so in 1880 as well. Close to the lake, however, there are concessions to modern times in the form of a children's play area with mini Honda bikes, a kiddies castle, roundabouts, swings and slides. A brightly coloured old aeroplane towers above this area, a Viking 700, which was in service from 1952 to 1972 and in which Winston Churchill, the country's war time Prime Minister, flew. Today children are permitted to sit in the cockpit, go down the escape chute and sit in the passenger seats of this old aircraft, now in the livery of the Saltwell Airways. Close by is the North Lodge, built in 1882, and still used as a residence, and, in the same style, another house now used as the base for the Parks Department staff. Next door is the small animals house and not too far away a well designed infants' play area, with a home for goats and chickens, amidst well appointed flower beds ablaze with colour in the summer.

This then is the Salte Welle Park of over a century ago and the Saltwell Park of the present day.

|

|

Amen Corner

Amen Corner, at the junction of the old High Street West and Gladstone Street, c.1925. The presence of three churches, United Free Methodist church, Bellevue Terrace, Baptist church, Gladstone Terrace, and Presbyterian church, Durham Road, gave rise to the name Amen Corner. Much of this area was demolished in the 1950s and '60s to make way for the Gateshead highway.

|

|

Whinney House (above left)

This was built around 1836 for the Joicey family, and was the largest house built in Low Fell. The most notable member of the family was James Joicey (1846-1936) elected MP for Chester-Le-Street in 1885, holding onto his seat until the election of 1906, then being created the 1st Baron Joicey.

Following the death of her husband in 1936, Edward Joicey's widow Eleanor, continued to live at Whinney House until her death in. The house was then let by the Trustees to a Mr. Fraser who was a colliery owner at Morpeth. In 1913 the house became the first Jesuit establishment in the Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle since the Reformation and was re-named St. Bede's Catholic Retreat. Its purpose was to attract workers from the shipyards and industry of Tyneside to meditate

and have quiet reflection upon spiritual matters. The retreats lasted for three days and the house could accommodate twenty three men.

In 1915, the house became a convalescent hospital for wounded soldiers of the First World War. In 1921 the house and grounds were purchased from the trustees by Gateshead Corporation and served the local community as a hospital, first for tuberculosis sufferers and then for old people. having been transferred front the Corporation to Gateshead Health Authority on reorganisation of services in 1974. More recently it has served as an administrative base and centre for people with learning disabilities, the Headquarters of Gateshead Health Care Trust and is presently being used by the Gateshead Jewish College. (pictured above right)

|

|

1832 strike and the battle of Friars Goose

The mine owners had one aim - to smash unionism in the north east. In 1832, they refused to sign on union members and a strike began.

In May 1832 a major disturbance took place at Friar’s Goose. As mine workers refused to work underground, 42 lead miners from Cumberland were brought in. Local miners pelted the incomers with stones and rubbish and two men were seriously injured. The miners refused both to work and to leave their cottages. On 8 May 1832 the part owner and manager of Friar's Goose collieries led policemen in an attempt to persuade rebellious pitmen that the cottages they lived in belonged to the colliery. He pointed out that if they did not work they had no right to occupy the cottages.

Ann Carr, a miner's wife and resident of Friar's Goose, is evicted from her home (above left) after shouting 'Union for ever' whilst the local men are forcibly restrained by officers of the law. These events of 4 May 1832 became known as 'The Battle of Friar's Goose'. Pitmen encamped in temporary shelters (above right) having been evicted from their cottages. Special constables were sworn in to deal with the emergency . Several families were evicted from their homes. This enraged the miners and brought in support from pitmen in Heworth and Windy Nook. Eventually the constables fled. .

The Rector of Gateshead, John Collinson was unable to deal with the affray and appealed to the Mayor of Newcastle for support. Reinforcements arrived and confronted the striking mineworkers. In the conflict which followed guns were fired and five mineworkers and two policeman were injured. The town marshal from Newcastle sent for more reinforcements and also called out the military. In July, Cuthbert Skipsey, a miner from North Shields, whilst trying to restore order, was shot by a constable.

Eventually the strike petered out. Whilst most of the miners eventually regained employment, the leaders of the strike became scapegoats and were outlawed. The Union crumbled and their leader Thomas Hepburn was banned from the coalfield.

|

|

Bottle Bank pictured above left in the 1930's and above right as it is today.

Bottle Bank, (It was sometimes erroneously called 'Battle Bank'), formerly included the whole distance from near the end of the bridge to about the railway arch over High Street. Its present cognomen must have been conferred at a very early period. The word bottle is Saxon, meaning a house or habitation and thus carries

us back to the earliest settlement at Gateshead, of which it also defines the locality. The same word occurs

in such Northumbrian place-names as Harbottle, Newbottle, Shilbottle, and Wallbottle.

In old documents the

west side of Bottle Bank is called West Raw, whilst the opposite side is styled East Raw, and the road itself

is the Via Regia. It was not only the royal road, but till the year 1790, when Church Street was formed,

the only road to and from the bridge of Tyne. Every stage-coach and waggon which traversed the

great north road was compelled to ascend and descend its steep gradient.

It was not named until 1826 and for many years was simply referred to as 'The New Street'.

As Bottle Bank was the part of Gateshead first inhabited, so it maintained pre-eminence through many centuries. In the old parish accounts the cost of its repair is an ever-recurring item. The Bank was indeed at one time the great burden of the burgesses. When Charles I. was on his way to Scotland to be crowned he passed through Gateshead.

The Hilton Hotel, built in 2004 and Tyne Bridge approach roads have replaced most of this area.

|

|

The Blaydon Races

If one you westward along the banks of the River Tyne through Blaydon, you soon comes to the huge Stella Power Station (pictured right, prior to its demolition in 29th March 1992) in front of which is a green grassed field, one of the many sites of the Blaydon Races. And the others? Well, perhaps, we should start the Blaydon Races story at the end, which is not quite as ridiculous as it at first sounds.

Despite the great fame of the song, how many who hear it really know very much about the actual Blaydon Races?

The year was 1916, the middle of the First World War, which had caused the cancellation of all horse racing meetings throughout the country. The full production of the Armstrong Whitworth's factory on Scotswood Road had been turned over to the machines of war. But because the factory had been so successful and the workers had strived hard for nearly two years, they were allowed to have two days' holiday, during which they were permitted to have a two-day race meeting at Blaydon on Friday and Saturday, 1st and 2nd September. The Friday meeting had been a huge success and on the Saturday morning the sun was still shining as it had been on the previous day. So thousands made their way to Blaydon Races, the thought of a second day's excellent sport being uppermost in their minds. As the racegoers watched the first race of the day, none of them could possibly have realised that they were watching the end of the Blaydon Races.

But the date quoted in the song, 9th June, 1862, was not anyway near the start of the Blaydon Races. They were started by the keelmen of Newcastle who, every Christmas, went sword dancing to raise money to be used as a prize for the Keelmen's Purse, a race for both horses and donkeys, which was held every year during the Hoppings (the local fayre) on the Guards at Blaydon. As the years went by the keel men became fewer in number as the work on the keels (boats) on the River Tyne became less needed. Consequently they found increasing difficulty in raising enough money. Perhaps the races would have ended because of that, but it was the coming of the railway to Blaydon which eventually caused it, because it was built on that flat piece of land that was the racecourse.

So from 1836, when the station was built, the races were forgotten for twenty six years until a small group of people decided to revive the event. They realised that they could draw quite good crowds if they sited the racecourse somewhere within easy reach of Blaydon Station (pictured above left) and, if possible, with easy road and river transport. They found the ideal site right in the middle of the River Tyne. Blaydon Island stands in the river close on the north side to the small hamlet of Bell's Close and on the south side to the factories near to the Scotswood Bridges. Today the site is mainly occupied by the works of the Anglo Great Lakes Corporation covering close on one hun¬dred acres. In the mid nineteenth century it was an ideal grassy place.

So on Whit Monday, 20th May, 1861, the Blaydon Races re-started. The racegoers travelling by rail to Blaydon Station came across a row of barges to the island, whilst the horses waded across the Tyne at Bell's Close. Special trains were laid on and a race omnibus ran from Newcastle. Several steamers made the journey from the river mouth at Shields. The re-opening day was a huge success and the local press afterwards carried numerous accounts of the event. Tucked away at the bottom of the page was another item, given very little prominence. It told of a concert at the Mechanics' Hall at Blaydon featuring comic and sentimental songs by a certain Mr Ridley. No one at the time was to know that it was the same Mr Ridley, who would later go down in history for the fact that everyone knows about the Blaydon Races, locally, nationally, and internationally. Geordie Ridley had attended the re-opening meeting and shortly before the following year's meeting wrote the song, which he sang a week before that meeting, which took place on 9th June 1862.

He sang it at the Wheatsheaf Music Saloon, better known after its landlord as Balmbras. It was from there that the buses ran to the races. The bus in Geordie Ridley's song was Parker's Horse Drawn Omnibus and the events predicted in the song actually took place, it is believed, in 1861 and not in 1862, for the song had already been sung before the second Blaydon Races. From the Cloth Market the bus moved along

Collingwood Street, which was not too different from what it is today. It then turned into Scotswood Road past Armstrong's factory and onto the Robin Adair, not the now rapidly deteriorating closed building near Scots wood Bridge, but much closer to Newcastle town. And, as the song tells us, at the railway bridge the bus wheel flew off. Speedy repairs were made and the bus continued its journey to Blaydon Races, while the injured went the other way to the Dispensary, to Dr Gibbs' and to the Infirmary. Dr Gibbs was one of Newcastle's best known doctors, who had his surgery at the bottom of Westgate Road. Gibbs' Chambers is still there today next to the Savings Bank, but the infirmary, sited at the car park close to the new Redheugh Bridge at the Newcastle end of Scotswood Road, has long since disappeared. The Dispensary, a small building in City Road close to the Pilgrim Street roundabout is also no longer there.

Still, as the song says, twenty-four people did carry on to the Blaydon Races. Paradise was a delightful place in those days. The River Tyne was clean, so clean that salmon were frequently caught in the reaches of the Tyne close to Blaydon. Armstrong's factory at Elswick (the Scotswood factory had not yet been built, nor had many of the rows of houses stretching up the hill from Scots wood to house the factory workers) was one of the few buildings around. The banks were covered in grass, woods and flowers. Streams flowed down into the River Tyne and animals roamed undisturbed while children played nearby. Horse-drawn traffic trundled along the cobbled road that went to Blaydon Races.

Today only the name remains although the area has been considerably cleaned up in recent years. On the river side, the railway line which took the racegoers to Blaydon Station has been pulled up and the narrow stretch to the river is being developed as an attractive industrial park.

So Parker's Horse Drawn Omnibus continued along Scotswood Road, across the Suspension Bridge, replaced now by a modern one, and right into Blaydon Town. The Chain Bridge, built in 1831, was pulled down in 1967 and the Mechanics' Hall at Blaydon at the end of the 1970s, whilst, of course, Jackie Brown is long since dead. Oh, yes, he was a real person, quite a character in fact. He was, as the song says, the bellman of Blaydon. He was also the town crier and the verger at the Parish Church of St Cuthbert. But none of these jobs brought him any money. This he received from doing a little advertising for various individuals and firms. Geordie Ridley employed him frequently to persuade people to go and see his show at the Mechanics' Hall. So the twenty-four passengers alighted from the coach and made their way across the barges to Blaydon Island. Here they saw four races in all but the afternoon was a disaster. The first race had been due to start at half past two but shortly after midday torrential rain began and by the start of racing the place was a quagmire. Only one horse, Royal Oak, had managed to cross to the island, the rest being stranded on the bank by the rising of the river.

Incidentally, Geordie Ridley had written his song before this time so could not have possibly known about this storm and yet one verse mentions it, so it must have been added later than 1862 when the song was

first sung at Balmbras Music Hall. Coffee Johnnie had a right to ask 'we stole the cuddy?' because the horses did not arrive until after four o'clock. Coffee was an amateur boxer, John Oliver, by name and when he died in Blyth in 1900 his body was brought to Winlaton churchyard to be buried with all his racing compatriots.

By the time the four races were run most of the people had left the island and travelled home.

Two years later the Blaydon Races stopped for the second time and the island in the river was deserted once more. Colonel John Cowen had been in charge of the races on Blaydon Island and he always looked forward to starting them for a third time. As he owned Stella Hall on the south bank of the river not far from the island this seemed as good a spot as any to try yet again in 1887.

On this site the Blaydon Races continued until 2nd September, 1916. On that day crowds congregated to watch another day's sport, celebrating the success of their hard work at the Scotswood Road factory of Armstrong Whitworth. What the crowd saw was the first race which turned out to be the last one. Anxious Moments, the favourite, won by a comfortable six lengths but was disqualified for carrying wrong weights. People looking forward to their winnings were to get nothing.

The munition workers, the miners, the soldiers on leave rioted and fought amongst themselves. Booths were shattered, buildings were destroyed and it soon became pretty obvious that no further races would take place that day. The horses were led quietly away from Stella Haughs to await another year. At that particular moment no one knew that the Blaydon Races had come to an end. As a local comedian said in a song he wrote and sang to the tune of the Blaydon Races

Oh, me lads, nee more yee'll see us gannin

To pass the folks on Scotswood Road

There's never nee one stannin.

There's nee more lads and lasses there,

Ne one te taak their places.

There's not much left of Scotswood Road

And nee more Blaydon Races.

So said Frankie Burns, and so say all of us.

|

|

Joseph Swan (31 October 1828 – 27 May 1914)

Joseph Wilson Swan was born at Pallion Hall in Pallion in the Parish of Bishopwearmouth, near Sunderland. His parents were John Swan and Isabella Cameron.

He eventually lived at Underhill on Kells Lane Gateshead (pictured above right). His laboratory was the first to be lit by an electric bulb and his invention was demonstrated in 1879 at a meeting of the Literary and Philosophical Society. The building is now used as a nursing home.

He became a British physicist and chemist, and he is most famous for inventing the first incandescent light bulb. Swan first demonstrated the light bulb at a lecture in Newcastle upon Tyne on 18 December 1878, but he did not receive a patent until 27 November 1880 (patent No. 4933) after improvement to the original lamp. His house ‘Underhill’ (in Gateshead, England) was the first in the world to be lit by lightbulb, and the world's first electric-light illumination in a public building was for a lecture Swan gave in 1880. In 1881, the Savoy Theatre in the City of Westminster, London, was lit by Swan incandescent lightbulbs, the first theatre and the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity.

Swan was one of the early developers of the electric safety lamp for miners, exhibiting his first in Newcastle upon Tyne at the North of England Institute of Mining Engineers on 14 May 1881. This required a wired supply so the following year he presented one with a battery and other improved versions followed By 1886 a lamp with better light output than a flame safety lamp was in production by the Edison-Swan Company. However, it suffered from problems of reliability and was not a success. It took development by others over the next 20 years or so before effective electric lamps were in common use.

In 1894 Swan was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, and in September 1901 he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) from theUniversity of Durham. In 1904 he was awarded the Royal Society's Hughes Medal, and made an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society. In 1904 Swan was knighted by King Edward VII, he also received the highest decoration in France, the Légion d'honneur, when he visited an international exhibition in Paris in 1881. The exhibition included exhibits of his inventions, and the city was lit with electric light, thanks to Swan's invention.

Swan died in 1914 at Warlingham in Surrey.

|

|

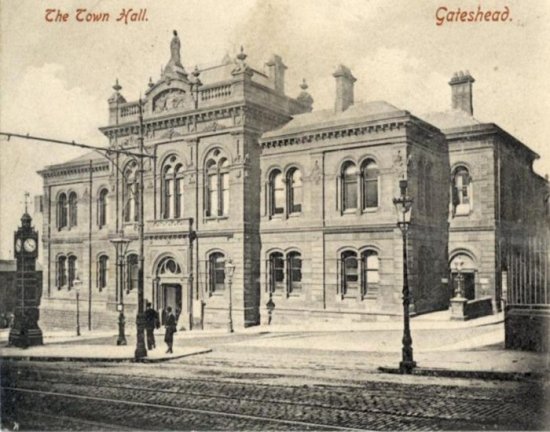

The town hall, built 1868-1870, was the third building in Gateshead to be designated 'Town Hall' and the largest and most expensive. It has survived slum clearance, a re-modelled 1960's shopping centre and a new Civic Centre and stands today as an emblem of Victorian civic pride. Currently being restored to its former grandeur, it has been a venue for council business, entertainment with a purpose built music hall and law enforcement with the provision of a police court and cells at the rear of the building.

Gateshead Council was formed following the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. Prior to this date, town government was the responsibility of the Four and Twenty - a close or 'select' vestry which operated from St Mary's Church. The first meeting of the Council was held on Boxing Day 1835 at the office of Joseph Willis on the West Street. On New Year's Day 1836, their second meeting was held at the Anchorage school attached to St Mary's Church when George Hawks was elected Mayor and William Kell was elected Town Clerk.

Early Premises

Early Premises

Although early meetings continued to be held in the Anchorage, from 20 January 1836 to 9 November 1844 the council rented a house on the west side of Oakwellgate as Town Hall and Police office premises. The council then purchased Greenesfield house from Edmund Graham for £1,300 in 1844 on a site near the railway station. Unfortunately this had to be demolished when the building of the Team Valley Extension Railway began in 1867. As a result, in June 1867, an Act of Parliament was passed authorising the Council to raise further monies to erect new premises. This allowed the Council to purchase land in Gateshead and to erect a new Town Hall, Police Court and County Court. In the event, Sir Walter James, later Lord Northbourne, gave the land on which the town hall was built.

The New Building

After an arduous process and a competition, John Johnstone of Newcastle was eventually appointed to be the architect of the new town hall.

Whilst the town hall was being built, the council had to use temporary premises in the Queens Head yard off Bottle Bank which they rented for £50 per year.

Construction of the Building

The Gateshead Observer of 29 February 1868 carried an advertisement "Applications for the Office of Clerk

of the Works, at the GATESHEAD NEW TOWN BUILDINGS (stating age and previous employment)

are to be sent to Mr.J.W.SWINBURNE, Town Clerk, Gateshead, on or before Monday, the 9th of March 1868. The Salary is £2. 10s per week, and the person appointed will be required to devote his whole time to the duties"

A Mr Burnup was appointed to the post.

Excavations for the town hall began in April 1868 On the 4 April 1868, the Gateshead Observer reported "A few men started at the west side of the site, and can now be seen diligently removing the accumulation of rubbish lying on the ground", and within two months preparations were being made for the laying of the foundation stone.

Foundation Stone Ceremony

The foundation stone was laid on 11 June 1868 - not without incident. Officials assembled at the Queen's Head Yard at 2pm for refreshments then proceeded to the town hall site at which two special platforms had been erected.

The Mayor, Robert Stirling Newall was presented with a silver trowel to lay the foundation stone. Shortly after this, whilst speeches were still being made, a loud creaking noise was heard as one of the platform began to collapse causing about 500 people to fall. It took a quarter of an hour to remove everyone. About 20 people were injured and were taken to the Dispensary. Although most injuries were slight, there was a fatality - a Mr Barnet of Windmill Hills, who died on 11 August aged 70 after suffering a blood infection following bruising to his feet. Further trouble was to be experienced during excavations when a coal seam was discovered - this may have been a residue of the old Conduit Pit which ran along the middle of Gateshead High Street.

Work progressed however and on 20 May 1869, it was announced that "the Chief Constable has taken possession of the portion of the building intended for the use of the police and the police court will be ready for occupation by the Town Council prior to the Council meeting in July". Six ornamental street lamps were erected outside the town hall. The building was now almost complete but the interior still had to be completed. The total cost of the building was £12,000 of which £10,000 was raised by a loan to the Council.

Furnishinqs

The contract for fitting out the Public Hall and the Council Chamber was awarded to Messrs Harrison and Howes. They provided tenders for £138. 5s for the hall and £50. 18s for the Council Chamber.

50 cushions were purchased from Bainbridges of Newcastle for the reserved seats in the music hall (presumably others simply had to sit on hard wood! ) Cocoa matting used for the flooring was supplied by Mr William Snowball at a cost of 2/2 (11 p) per sq yard.

The Building Opens

In January 1870, John Johnstone made a final inspection and approved the building. The Town Hall was opened officially on 5 February 1870 and celebrated with a dinner for about 100 guests chaired by the Mayor of Gateshead, Ald. Brown. Guests included Lord Ravensworth, Archdeacon Prest, Walter C James, Sir William Hutt (Gateshead's MP), Joseph Cowan MP, together with the Mayors of Newcastle and South Shields plus John Johnstone the architect and John Elliott chief constable.

In March 1870, William Telford of Newcastle was appointed Town Hall keeper at a salary of £1 per week together with accommodation, and free coal, gas and water.

On the north side of the building was the residence of the Superintendent of Police & the fronts of the Police Court. The main interior parts of the building were the Council Chamber on the first floor, the Music Hall which held 1,000 people on the ground floor, and the Police Court. For over 100 years, this building was destined to be the main centre for Council activities.

Gateshead's Old Town Hall is now a venue for conferences, gigs and concerts, complementing the facilities of the Sage. A former Victorian bank and library are close neighbours built in similar style.

Gateshead Town Hall's civic role as home to the town's council was superseded by a modern Civic Centre. Gateshead's Civic Centre lies along the road to south of the Old Town Hall between West Street and Prince Consort Road. It is a red brick building built by the Borough Director of Architecture D.W Robson from 1978 and 1987.

|

|

The Ginger Bread House

The cottage at 'Old Robber's Corner' (pictured above c1900) was once the lodge of Park House and stood on Sunderland Road to the east of John Street. There is some debate as to the name; one story suggesting that this was an isolated area frequented by highwaymen.

Another possible explanation refers to the fact that 'robber' is a slang term used for the thistle plant, and this area was known to be covered with thistles. The origin of the name of the house ‘Ginger Bread’ is again a matter for speculation. The house was demolished around the turn of the century.

In the background, the house on the right is Ford House.

|

|

Sodhouse Bank

Sheriff's Highway, Sheriff Hill, photographed in the 1950s. The road was originally called Sodhouse Bank after the many huts constructed by tinkers out of turf or sod that lined the street.

Sheriff Hill is so named because in the thirteenth century it was the meeting place of judges of assize and the sheriffs of Newcastle. The mock-tudor fronted building is the Three Tuns.

|

|

Sheriff Hill (pictured above in the early 1920’s and as it is today) is a suburb in the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead in Tyne and Wear, England. It lies on the B1296 road 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Gateshead, 2.5 miles (4.0 km) south of Newcastle upon Tyne and 12 miles (19 km) north of the historic city of Durham. According to the 2001 UK census it had a population of 5,051.

Until the 19th century, Sheriff Hill was part of Gateshead Fell, a "windswept, barren and treacherous heath" that took its name from the town of Gateshead and the fell or common land contiguous with it.

In 1068, Malcolm III of Scotland marched across the Scottish border to challenge the authority of William the Conqueror. Malcolm, accompanied by native insurgents and foreign supporters, was met by William's men in the area of Sheriff Hill and was decisively beaten. In the 13th century, a road through Gateshead Fell became the main trade route between Durham and Newcastle and as its importance grew, two public houses – the Old Cannon and The Three Tuns, were built along with a small number of houses.

The settlement's name derives from the Sheriff's March; an ancient, biannual procession first held in 1278. An inquisition at Tynemouth declared that the King of Scotland, the Archbishop of York, the Prior of Tynemouth, the Bishop of Durham and Gilbert de Umfraville, Earl of Angus should meet the justices before they entered Newcastle from the south.

A procession was held before the meeting; on the appointed day the procession started in Newcastle, crossed the River Tyne to Gateshead and made its way up the steep road. The meeting place was initially at Chile Well but subsequently the procession came to "light and go into the house". The house was the Old Cannon public house, where drink was served at the sheriff's expense. When the judges arrived, the procession returned to Newcastle.

By the 1830’s, Gateshead Fell had been enclosed and a village had grown around the road, largely populated by an influx of tinkers, coalminers working at Sheriff Hill Colliery and workers at the local pottery, mill and sandstone quarry. In 1819, an explosion tore through the Sheriff Hill Colliery killing thirty-five people. By the turn of the 20th century these industries were in steep decline. The local authority built a large council estate at Sheriff Hill to alleviate dangerous overcrowding in Gateshead, effectively turning the area into a residential suburb. It ceased to be an independent village on 1 April 1974 when it was incorporated into the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead under the terms of the Local Government Act 1972.

Now part of the local council ward of High Fell, the suburb is economically disadvantaged compared with other areas of the borough and nationally, with high levels of unemployment. Sheriff Hill was the site of one of Gateshead's largest boarding schools but as of 2012, the only remaining educational establishment is Glynwood Primary School.

The suburb also contains the Queen Elizabeth Hospital – the largest hospital in Gateshead, a small dene and a small park. The principal landmark is St John the Evangelist Church, one of three Grade II listed buildings in the area and one of two remaining churches. The southern end of Sheriff's Highway – the main road through the suburb, is more than 500 feet (150 m) above sea level, making it the highest point in Gateshead.

|

|

Dunston Staithes

Dunston Staiths were built by the North Eastern Railway in two stages; the first staith with three berths was opened in 1893. A second similar staith was opened in 1903, immediately to the south, and a basin dug out of the riverbank to service it.

There were six berths, and loading could be carried out at any state of the tide; three electric conveyors and twelve gravity spouts. Record yearly shipment was 5½ million tonnes. The second set of staiths was taken down to the top of the piles in the 1970s and then further dismantled in the 1980s. However, the majority of the structure survived intact and was restored for the Gateshead National Garden Festival in 1990.

The staiths were the last working timber staiths on the Tyne. The wooden staithes were closed in 1980 and abandoned with the demise of the coal industry and have since fallen victim to vandalism, they were severely damaged by fire during the night of 19/20 November 2003 (pictured above right).

The Dunston Staithes in Gateshead played a crucial role in the transport of millions of tons of coal, in recognition of that The Heritage Lottery Fund has awarded almost £420,000 to restore the landmark and open it up to the public for the first time.

Statistics are: 1,709ft long, 50ft wide and 40ft high – reputedly the largest timber structure in Europe (and possibly the world). Total weight of timber: in excess of 3,000 tonnes, Cost: £120,000+, Materials: North American Pitch Pine, Shipped 1.5 tonnes of coal in first year, Peaked in 1939 with nearly 4 million tonnes shipped, Operations ceased in 1977, and structure closed in 1980, Centrepiece of Gateshead Garden Festival in 1990.

|

|

Holy Trinity Church Gateshead High Street, formerly St Edmunds Chapel and Hospital

St Edmund’s Chapel was dedicated to Edmund of Abingdon, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1233 to 1240, who was canonized in 1246. Around 1248, Nicholas de Farnham, Bishop of Durham founded a chapel and hospital, of which St Edmund’s is the surviving building. The hospital was chiefly intended for the ‘refreshment of the soul’. A master and three priests were appointed to celebrate four masses every day. Mediaeval hospitals also cared for the sick and aged, the poor and the pilgrim, but St Edmund’s Hospital records are silent on this aspect of its work.

By 1325 buildings included a buttery, kitchen, brew house, granary, byre, pigsty and the chapel which would have been the focus of life.

In 1448 the chapel passed into the hands of the nuns of St Bartholomew, Newcastle. They had run into financial difficulties and the Bishop of Durham appropriated to them the hospital and all its possessions on condition that the nuns provided two chaplains to celebrate in the chapel, kept the buildings in good repair, and paid a yearly pension to the Bishop and Prior of Durham.

When the monasteries were dissolved by Henry V111, the nunnery and its lands were surrendered to the crown. This was in 1540, and for two centuries the history of St Edmund’s Chapel is closely associated with two families, the Riddells and the Claverings.

William Riddell was related to the last Prioress by marriage and he bought the hospital lands and built a mansion just to the east of the chapel in the late 16th century.

The next generation of Riddells converted to Roman Catholicism and the mansion became a centre for Jesuit mission. The Claverings were also staunch Roman Catholics, and a succession of chaplains served in the private chapel within the mansion. The Chapel was not used for worship. In those times of intolerance and persecution, that would have been too dangerous. In 1746 the mansion was burnt to the ground by an angry mob.

Gateshead’s population grew and ironically, the Chapel was threatened with demolition in the 1880’s because a bigger building was required. Instead of demolition, the north wall was removed and the chapel turned into the south aisle of a new church dedicated to the Holy Trinity in 1894-6. Holy Trinity was declared redundant in 1969 but the Chapel was partitioned off and used for weekday services and private prayer. Sunday services restarted in the Chapel in 1981 after the parish church of St Mary’s was destroyed by fire. It reverted to its original name of St Edmund’s Chapel.

The Victorian addition to the church was leased to Gateshead Council and became Trinity Community Centre

Medieval Remains

Holy Trinity Church on the High Street, photographed above left in 1893 and on the right as it is today. The oldest part of the building on the right is St. Edmund's Chapel, one of two medieval buildings in the town. After the reformation, the building fell into ruin and in 1836 the land was given by Cuthbert Ellison to the Rector of Gateshead. Public donations enabled the construction of Holy Trinity Church in 1837.

St Edmund's Hospital Chapel, now Holy Trinity Church, stood among trees in a field, a picturesque ruin. Nearby, Park Lane lived up to its name, passing between fields to Park House and its estate. There were further scattered houses along High Street; one small terrace on the west side was called Pleasant Row, probably indicative of a pleasant place in which to live. To the east of the junction of Sunderland Road and High Street were two reservoirs that supplied some of the town with water. There had been ponds on this site, filled by a stream flowing from the west called the Busy Burn. This area is now covered by the Al flyover and the now derelict All Saints School and playing field. Further south, opposite the Five Bridges Hotel, stood King James' Hospital, which was in fact an old peoples' home, an institution which still exists: new buildings have been opened on Sunderland Road. This part of High Street, known then as Brunswick Street and now Old Durham Road, was the site of St Edmund's Church, while the land between the old and new Durham Roads was an extensive market garden.

|

|

The Parish of Lamesley

In 1870-72, John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales described Lamesley like this:

LAMESLEY, a parochial chapelry in Chester-le-Street district, Durham; on Urpeth burn and the river Team, 4 miles S of Gateshead station. Post-town, Gateshead. Real property, £13,075; of which £6,373 are in mines, £112 in quarries, and £1,000 in railways. Pop. in 1851,1,914; in 1861,2,233. Houses, 366. The property is divided among a few.

The manor belongs to Lord Ravensworth. There are extensive collieries, beds of ironstone, and quarries for grindstones. The living is a p. curacy in the diocese of Durham. Value, £138 Patron, Lord Ravensworth. Pictured above the former Almshouse, In 1932 they were described as "modest and retiring, typical of the quiet and rest of old age". On the front of the building was the inscription "Anno Domini MDCCXXV. These almshouses were built and endowed by Maria Susanna Ravensworth in memory of her two departed children. It is good for me that I have been afflicted that I might learn thy statutes, CXIX Psalm, lxxi verse". The almshouses were home to eight poor women.

The church was rebuilt in 1759; has a tower of 1 821; and contains a carved pulpit. There are chapels for Wesleyans and Primitive Methodists, national schools, and charities £40.

CHAPELRY OF LAMESLEY.

The Chapelry of Lamesley is bounded by the Parishes of Whickham and Gateshead on the North, by Gateshead and Washington on the East, by the parish of Chester-le-Street on the South, and by Whickham and the Chapelry of Tanfield on the West.

The Chapelry includes four Constableries: 1. Lamesley; 2. Ravensworth; 3. Kibblesworth; 4. Hedley.

Lamesley.

Lamesley lies in the vale to the South East of Gateshead Fell. The descent of the manor is so connected with that of Ravensworth, that it is unnecessary to anticipate it. Lamesley formed the second Prebend in the collegiate Church of Chester founded in 1286. The Chapel is named as already existing in the foundation charter; on the dissolution a slight provision was reserved for a perpetual Curate. There is neither glebe nor parsonage.

The Chapel is entirely modern, and was rebuilt in 1759.

Tithes—The Chapelries of Lamesley and Tanfield pay tithe of lamb and wool only, to the Perpetual Curate of the Mother-Church of Chester-le-Street. The corn tithe of the Prebend of Lamesley belongs to Sir T. H. Liddell, Bart., and the small tithes generally to the Curate of Lamesley.

Lamesley Chapelry, not in charge nor certified—The Collegiate Church of Chester, Patrons till the dissolution; present patron, Sir Thomas Henry Liddell, Bart.

Lamesley station was on Smithy Lane, it closed 4/6/1945, the site on the up side is now the entrance to the saw mills, the down side was removed to make way for the northern extremity of Tyne Yard. There were station buildings on the original over bridge which was replaced by the current road bridge over the end of Tyne Yard. Middleton Press, Eastern Main Lines, Darlington to Newcastle has a photo and small plan.

Lamesley today is described as: A village and civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead, Tyne and Wear, England. The village is on the southern outskirts of Gateshead, near to Birtley. The parish includes Kibblesworth, Lamesley village, Eighton Banks and Northside, Birtley which is predominantly private housing in neighbourhoods named The Hollys, Long Bank, Northdene and Crathie.

A hilltop contemporary sculpture in the parish is the Angel of the North by Anthony Gormley on a minor hilltop which is lower than Low Fell in the parish.

Demography

Combined, this area has a population of 3,928 people as at the 2001 census and unlike the small rise in the overall region saw a decrease to 3,742 at the following census. The Gateshead MBC ward of Lamesley had a population of 8,662 at the 2011 Census.

The Parish Church of St Andrew Lamesley

The Structural History of the Church pictured above, although the church stands on a medieval site, it is generally seen as a building of the mid- 18th century subject to so much remodelling in the 19th century that Pevsner & Williamson (1983- 349) could claim that nothing remained visible of the original building. A detailed study of the fabric suggests that the story may be rather more complicated. A key piece of evidence is a surviving plan of 18251 which shows the church before its gothicisation. The body of the nave is clearly the same rectangular structure as stands today, but without either buttresses or arcades, and the chancel, again without buttresses, seems to follow its present plan. The nave is shown with galleries on north, west and south, approached by L-plan stairs in the western angles; it is not clear how the galleries were supported. The overall plan is interesting, as it is unlikely that a mid-18th century building would have had an elongate chancel such as this; the inference seems to be that the medieval chancel either survived, or had been rebuilt on its original footings. This situation is paralleled almost exactly at nearby Tanfield, another chapelry of Chester-le-Street. Here the nave was rebuilt as a ‘preaching box’, of similar form to that at Lamesley, in 1749, but ther plan and at least part of the fabric of the medieval chancel were retained. At Lamesley (as at Tanfield) the chancel was rebuilt, on its old footings, in the 19th century, although it is possible that some early fabric survives, perhaps in the north wall.

There certainly seems to be a discontinuity between the mid-19th century north-eastern buttress and the adjacent wall to the west; unfortunately the remainder of the wall is plastered or inaccessible within the roof spaces over the vestry and organ chamber. Mackenzie and Ross refer to a plain square tower being built in 1821, and this is shown on the 1825 plan. This was a short-lived construction, as when the church was remodelled, partly at the expense of Lord Ravensworth, c 1845 it was replaced by the present Gothic structure with its extraordinary solid stair turret, a peculiar conceit which may be linked to the benefactor’s tastes in extravagant medievalism, explicit in his nearby stately home. It would appear to be at the same time that the nave was remodelled with its present arcades and galleries, the addition of buttresses and the alteration of the windows to their present form.